By Ivan G. Goldman

If you look through the records of ex-fighter Anthony Fletcher’s murder trial it looks more like a Marx Brothers movie than an exercise of rational jurisprudence. You almost expect someone to pop out from behind a set and declare it was all a gag.

But the vaudeville antics of that trial and all that followed were no gag to Fletcher. Though facts prove him innocent, he still sits on Pennsylvania’s death row twenty years later.

In 1985 the U.S. Supreme Court, in its landmark U.S. versus Bagley ruling, declared that the prosecution’s mission “is not that it shall win a case, but that justice shall be done.” The Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office didn’t get the message, and after a judge in 2004 ordered a new trial for Fletcher, the D.A. still operated under the old adversarial principle. Under this theory, if the two sides go at it in a courtroom, the truth will come out and justice will prevail. To which any astute observer of the system would reply, “You’ve got to be kidding.”

In Fletcher’s case the police “lost” or threw away vital evidence that not even a mediocre homicide detective would dare to misplace, the prosecution concocted and embellished a fictional tale as it went along and successfully maneuvered to keep the medical examiner, whose testimony would have wrecked the case, away from the courtroom. The judge made one unforgivable error after another, and the court-appointed defense attorney sat practically mute through all of this, allowing, for example, hearsay testimony from a crack addict “witness” without raising an objection. He also failed to contact the medical examiner.

Then after losing a case no competent attorney would have lost, defense attorney Stephen Patrizio was asked to present any facts that might mitigate the death penalty, and he failed even to mention his client’s honorary discharge from the Army. Anyone who’s watched three or four of those old “Perry Mason” episodes could probably muster a better defense.

As you read through the trial documents you watch the prosecution become more and more daring as it gets away with more and more buffoonery.

Toward the end, Assistant District Attorney Mark E. Costanza claimed Fletcher shot Vaughn Christopher “once in the thigh, and then as the victim turned to get away, raised the gun and shot him in the back” – an account that’s utterly fictitious and contrary to all the physical evidence.

What’s more, the refuting evidence is so clear that when Judge John Milton Younge ordered a new trial, he concluded that Fletcher had been “sentenced to death primarily based upon evidence that has since been retracted by the office of the medical examiner.” To deny Fletcher’s petition on a “technicality or procedural error in such questionable circumstances,” Younge ruled, “would constitute a miscarriage of justice.” From a judge, that’s strong language.

Yet the state Supreme Court did precisely what Younge warned against, disregarding the facts and ruling instead on technicalities and procedure, an outcome so preposterous that it would have tested the boundaries of Groucho, Chico, and Harpo.

The autopsy report states Christopher was shot not in the back, as the prosecutor claimed, but in the thigh and the abdomen at severe angles, supporting Fletcher’s statement that Christopher pulled a gun, Fletcher tried to wrench it away from him, and Christopher was shot during that struggle.

(For readers who haven’t seen previous articles on Fletcher’s case, Christopher stuck him up, Fletcher saw him on the street later, confronted him and threw a punch. Christopher pulled a pistol.)

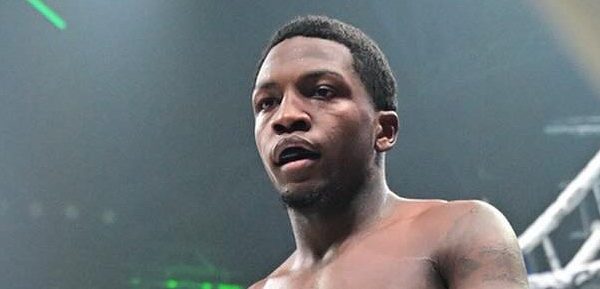

A competent defense attorney, Judge Younge noted, would have cited the principle of “grave risk of death” to explain Fletcher’s actions, yet Patrizio failed to do so. He also refused to let Fletcher take the stand. Fletcher suffered from Bell’s palsy, probably caused by punishment he took in hard-core Philadelphia sparring and 29 pro fights. It “left one side of his face permanently contorted and caused a speech impediment,” Patrizio explained later in an affidavit. “I feared that the jury might be repulsed by his appearance.”

Without arguing the facts of the case, the D.A.’s appellate division cited the legal principle that when a defendant becomes his own lawyer, that defendant can no longer complain of incompetent defense. In legal parlance, the D.A. maintained that the facts had been “waived” because Fletcher, for a time, tried to mount his own appeal. The state Supreme Court bought it, and the wording of its ruling was a clear attempt to deny all further appeals based on the evidence — an outcome that was arguably crazier than the original trial.

You would think that if Fletcher could somehow get his case into a federal court someone there would notice U.S. versus Bagley and decide that his innocence has at least some bearing on how the case should be decided. But it’s no easy matter to get his case moved outside the highly suspect Pennsylvania system, a system that for twenty years has been trying to solve the whole embarrassing question by killing Fletcher.

The current district attorney, R. Seth Williams, no doubt thinks he owes some allegiance to lawyers in his office, including those who may have participated in the frame-up. But if he were to check out his oath of office, he’d find none of his colleagues mentioned. He would find, however, references to the cause of justice.

Williams might also check out the work of Craig Watkins, a D.A. in Dallas, Texas, who’s been ferreting out wrongfully convicted inmates and getting them freed. Another avenue: Pennsylvania Governor Tom Corbett, who has the power to commute an unjust sentence and to pardon or exonerate a casualty of that injustice. A truly free country should never accept the terrible acts of its mindless or malevolent functionaries.

(My wife Connie Goldman again pulled essential legal materials from a mountain of court papers for this article, the fifth in a series. Fletcher’s address: Mr. Anthony Fletcher, #CA1706, 175 Progress Drive, Waynesburg, PA 15370.)

Ivan G. Goldman’s latest novel Isaac: A Modern Fable came out in April 2012 from Permanent Press. Information HERE