By Ivan G. Goldman

The 1992 autopsy of slain small-time crook Vaughn Christopher, the Pennsylvania medical examiner found, agreed with the account of former Philly lightweight contender Anthony Fletcher and directly refuted the bogus testimony of the prosecutors’ chief witness. But Fletcher was convicted and sentenced to death anyway.

Prosecutors made sure that Chief Medical Examiner Hydow Park, who’d performed the autopsy, never got on the stand. Park also wondered in his report why the dead man’s clothes weren’t tested for powder burns, a typical procedure in such a case. Powder burns would have confirmed the statement of Fletcher, who told police Christopher pulled a pistol on him out on the street and that Christopher was shot as they struggled for it.

The clothes, which had to be in the custody of police, mysteriously disappeared. Prosecutors never produced a chain of custody for them, an exceedingly strange omission that any knowledgeable defense attorney would have pounced upon. In another astonishing display of ineptitude, Fletcher’s attorney failed to interview Park, whose findings would have wrecked the case. They sat unused and wasted, much like the last twenty years of Fletcher’s life.

The case was loaded down with a staggering number of gaping holes and transgressions by authorities. For example, the judge’s instructions to jurors were gravely flawed, providing solid grounds for a mistrial, but because the flailing defense attorney failed to object, there was no way to raise the issue on appeal.

When I went over the facts with a savvy retired detective, he told me this looked very much like what racist authorities secretly label an “NHI” case. “Non-human involvement,” he explained. “Black on black crime.” Police and prosecutors assume everyone involved is a criminal and prosecute survivors regardless of circumstances. In extreme cases like Fletcher’s they illegally conceal or dispose of conflicting evidence.

In a deposition made after Fletcher’s trial, Park testified that the story told by the prosecution’s chief witness, who said Fletcher pulled a gun and shot Christopher from several feet away, was inconsistent with the steep trajectory of the bullet. The shot “is, therefore, more likely and more plausibly explained if there were a hand-to-hand struggle shortly after the gun was drawn at the decedent’s right flank, which could have occurred under Mr. Fletcher’s account, than if the shooting occurred, as Ms. (Natalie Renee) Grant said, with Mr. Fletcher shooting the decedent from some feet away as the decedent turned. If I had been called to testify . . . I would have given the opinion set forth above,” Park said.

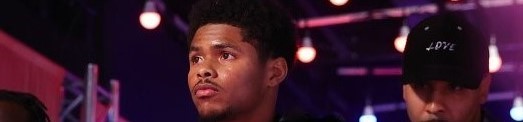

Had Fletcher not been an ex-prizefighter armed with superior reflexes, Park very possibly would have examined his dead body instead of Christopher’s. Fletcher had scored victories over Livingstone Bramble and Freddie Pendleton before retiring in 1990 with a record of 24-4-1 (8).

Park said prosecutors never informed him of the trial date, which was a jolting breach of protocol. The prosecutors, having watched Fletcher’s attorney blunder through pre-trial hearings and the plea bargaining process, calculated that they could get around Park by calling a subordinate, Ian Hood, to take the stand and try to read through Park’s notes. It worked. In a later deposition Hood admitted he misinterpreted those notes, and that he hadn’t understood the angle of the bullets were too steep to have been fired at a distance, as Grant testified. He also retracted his testimony that a bruise on the chest was probably caused by a bullet, as the prosecution contended. Later he agreed that the bruise was more likely to have been “inflicted by an elbow or a fist in the midst of a struggle,” confirming Fletcher’s statement.

Grant was looking to get out from under theft and prostitution charges hanging over her and to maintain custody of her daughter. Had she testified truthfully she’d have had to include the struggle for the gun in her account. Had the gun been Fletcher’s, then Christopher must have charged him to initiate the struggle, and that’s how she would have testified.

Also in his 2003 statement, Hood admitted under oath that he in fact was not licensed to practice medicine in Pennsylvania at the time he testified and had later been disciplined by the state licensing board for practicing and representing himself as someone who had the credentials to do so.

But facts proving Fletcher innocent, according to a Pennsylvania court ruling, are no longer relevant because Fletcher made legal errors when he filed his own appeals. The same legal system that failed to prosecute so much as one corrupt banker for pushing the economy over a cliff keeps boxing brother Anthony Fletcher buried alive in Waynesburg on “procedural” issues and may even put him to death one day, particularly if we forget about him.

(This is the third article in a series on Fletcher. Connie Goldman conducted invaluable research. Ivan G. Goldman is responsible for any errors.)

Ivan G. Goldman’s latest novel Isaac: A Modern Fable came out in April 2012 from Permanent Press. Information HERE