By: Oliver McManus

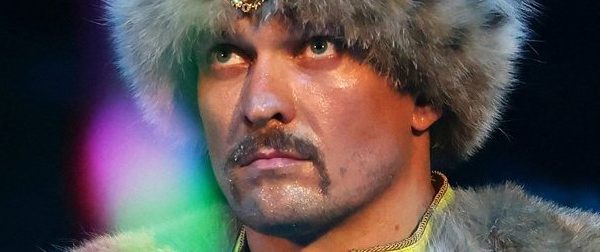

“I just didn’t do enough”, the immediate verdict from James DeGale following his loss to Chris Eubank Jr. Talking to Gabriel Clarke he offered a neat characterisation of not only the fight in question but DeGale’s underwhelming professional career as a whole.

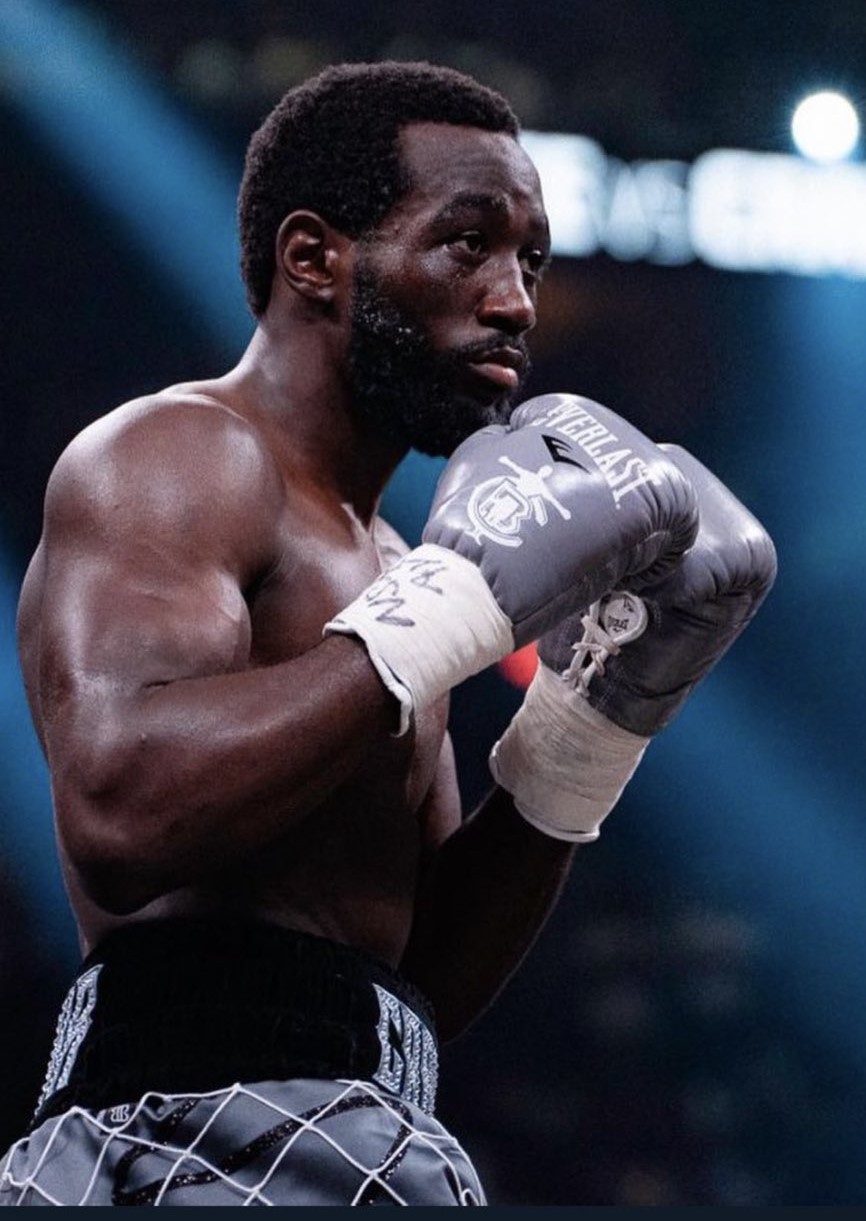

No-one can dispute the natural talent of Hammersmith’s premier boxing product but did we ever see the realisation of his capability as a pugilist?

Having turned professional with an Olympic gold medal freshly around his neck expectations were high. And rightly so. This is a man who had already cultivated a reputation, partly in thanks to his six-fight amateur series with Darren Sutherland, and EU Silver and Commonwealth Bronze medals also adorning his trophy cabinet. Such promise saw a, reported, £1.5million contract thrown his way by Frank Warren.

From the off DeGale seemed to be up against it with his debut fight – in February 2009, against Vephkia Tchilaia – being met with a splattering of disapproval due to the fact it lasted the full four rounds. Nothing particularly untowards about a shut-out win against a defensive journeyman but, for DeGale, he was expected to do better. He always has been, he was the talent of a generation.

Developed quickly, it would be in his ninth fight that Chunky planted a marker by knocking out Paul Smith – an established figure by the time of the bout – in the ninth round to rip away the British super-middleweight title. Perhaps, then, now was the time to sit back in expectation. From here on would be the time for judgement. The first occasion in which we could evaluate the progress of DeGale arrived shortly after with a grudge-match against George Groves.

Himself a graduate of Dale Youth, Groves had been forging a career of his own under the guidance, for a while, of Adam Booth. Crunch time came on May 21st and we all know how the fight fared. Close on the scorecards – 115-115, 115-114, 115-114 in favour of Groves – it was a gritty chess match if ever there was one. Groves utilising the superior movement and leading with a steady jab whilst DeGale sought to counter-punch. No disgrace in losing the contest.

The buildup to the bout showed, ultimately, a flaw from DeGale in failing to capitalise on his, how shall we say, less than warm personality. Personal as it sounds, it’s not a criticism of who he is but rather how he marketed himself. It was painfully clear that DeGale never really cared to be liked and, for him, boxing was about results not building a fan base. He said what he genuinely thought and in a manner only he could. What he didn’t do, however, was embrace his role as a villain.

In contests such as the one with Groves, you’re never going to out-talk or out-smart the opponent so there was no point in trying to do so. Even though Groves didn’t cover himself in glory, either, it was the older statesman who, ultimately, came across as churlish and arrogant. Not through some designed act in order to goad Groves or generate publicity but because of a desire to strike his own ego.

That prioritisation of self-satisfaction was evident from his attempts to crack the American market. Not that, in itself, that’s an issue but he never did ‘crack’ it despite his repeated success. Credit where credit is due, DeGale went to the States and won the IBF super-middleweight title, against Andre Dirrell, in the best win of his career. Two fights later and he was lined up for a unification with Badou Jack. At the time an imperious force to be reckoned with – how the years have seen him stutter in stardom – Jack was a foreboding test but one that DeGale rose to. A majority draw against the Swedish fighter that, hindsight suggests, took it firmly out of the British man.

It can certainly be claimed that performances on foreign soil never attract the same glamour or acclaim as they perhaps deserve but DeGale didn’t look on full form against Dirrell or, in subsequent defences, Lucian Bute (in Canada) and Rogelio Medina. The ambition for a fight, throughout his career, against a true behemoth of boxing such as Carl Froch and Andre Ward seemed to exist in verbals only. Imagine that – Ward vs DeGale. It’s frightening. Then, I guess, that’s why this article has come about. Perhaps the real James DeGale is still wandering around lost in Beijing and the man we’ve seen is just a poor imitation. In seriousness it isn’t only a case of never seeing the full potential of the man – and there are extenuating circumstances around that from lifestyle to injury – it is more the acceptance of mediocrity that pains me the most.

Lost in his own illustrious loyalty, a long term allegiance to trainer Jim McDonnell may well have proven to be the sticking point for Chunky. That doesn’t mean McDonnell is a bad trainer and far from it but after repeated performances where nothing seems to be clicking or flowing with fluidity then the clues are there that it might be time for a change. After a career of disappointing performances the message should have been blindingly obvious. Make a change, try something new. Nothing is stopping you from reverting back to the old afterwards.

Yet throughout his career you got the impression that for James DeGale simply being a belt holder was adequate, his stake at supremacy. An ever present frustration for British boxing fans was the fact that we never saw quite how good he could be yet we all had an idea of just how irreproachable his abilities were. Against Chris Eubank Jr, then, at the weekend we saw a laboured version of the man we, certainly I, admired. If that was the final act for the two-time world champion then, to be frank, I don’t think I want to see the encore.

The first British fighter to win Olympic Gold to go on to claim world glory in the professional ranks. Not just that but a British, European and International champion – across three governing bodies – he really did have a career to reflect on with pride. You suspect, though, the history books will likely not remember him in the fondest of terms for, such was his ability and promise, James DeGale never did quite enough.